This Total Revenue Primer marks the first edition in a multi-part series on the financial data of cities hosted on CityFinance.in. Each edition in the series will spotlight one key fiscal indicator, offering a focused analysis to demonstrate the different kinds of insights that can be drawn from the data and how they inform a deeper understanding of urban finance. This initiative aims to foster greater understanding and engagement with financial data of Indian cities, enabling deeper analysis and research in this critical area.

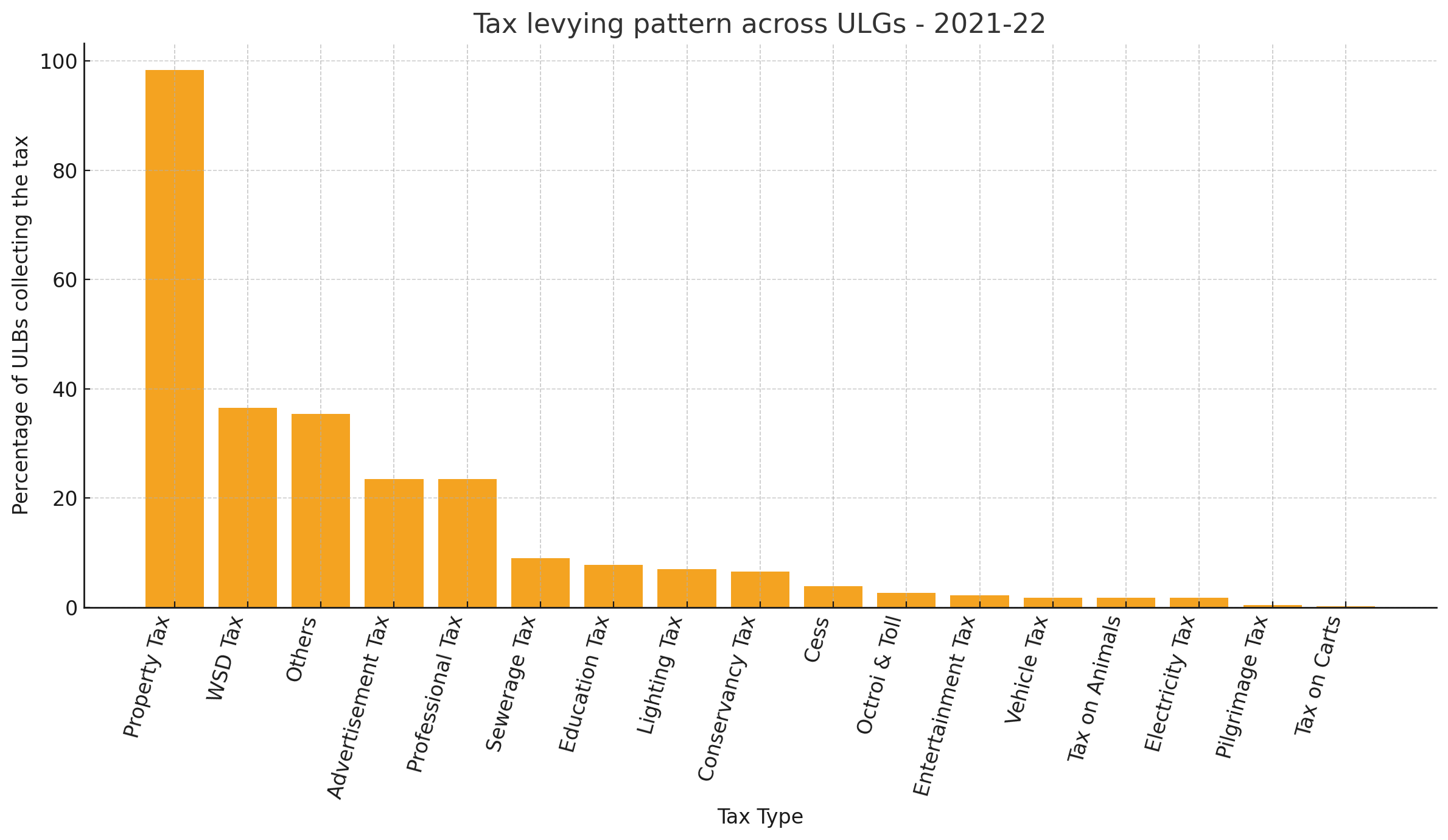

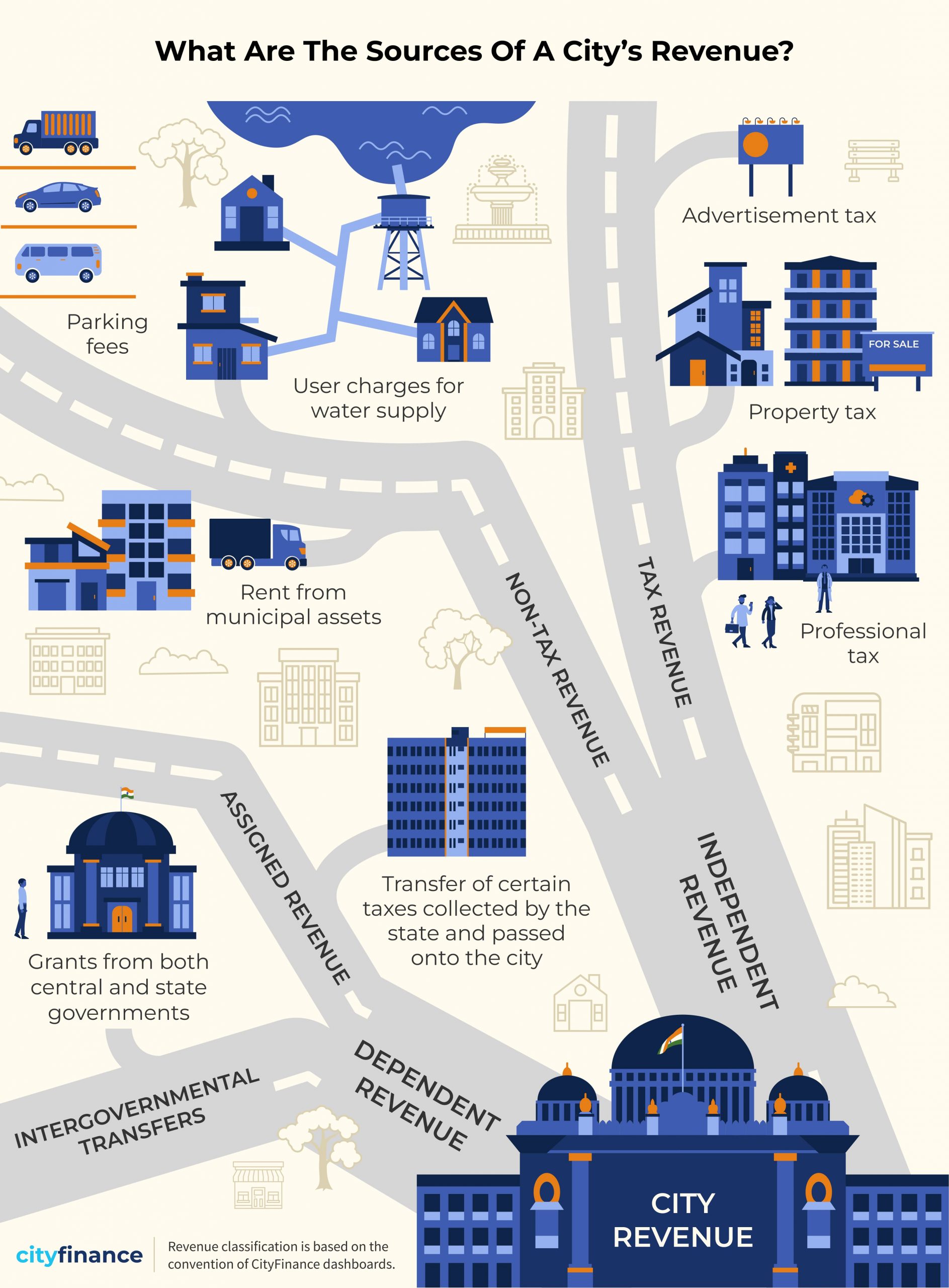

Total revenue refers to the aggregate income a city receives from all sources. Major sources of a city’s revenue include tax revenue, non-tax revenue, assigned revenues, and intergovernmental grants from both state and central governments.

Together, these streams form the financial backbone that supports a city’s operations and development initiatives.

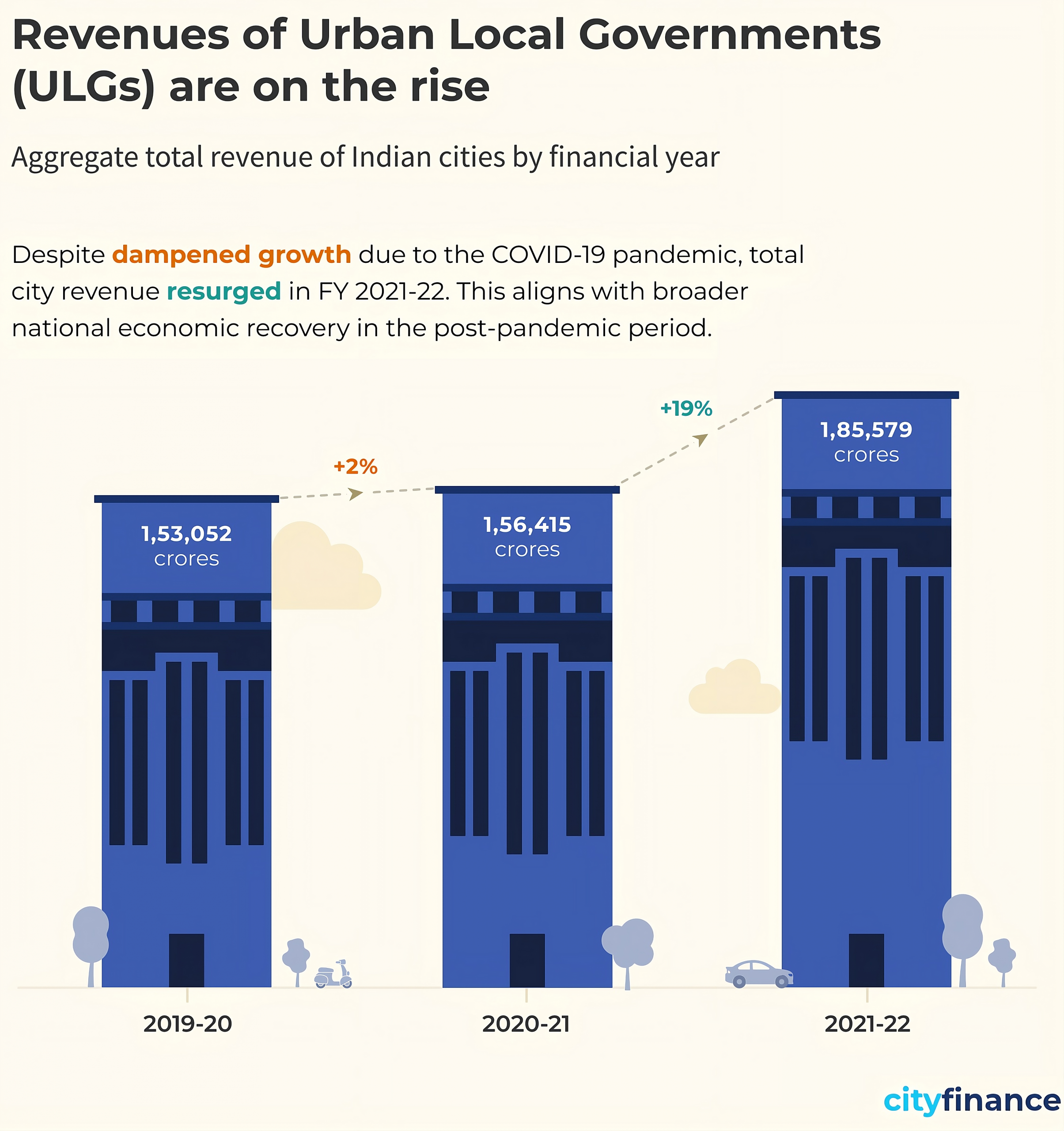

Rising Revenues, Widening Revenue Gaps

Revenues of Urban Local Governments (ULGs) are rising across India, reflecting positive economic growth. However, this increase is far from uniform, with significant disparities emerging between cities.

As we see in the chart above, the 7 cities that serve 17% of the urban population of India report the largest share of receipts at 42%. In comparison, 3,374 cities that serve 41% of India’s urban residents form just 16% of total revenue. Could bigger cities simply have higher revenue because of their larger population base, or does the trend hold even when we look at per capita revenue? Let us examine.

Larger cities generate significantly more revenue per person, with cities in the 4 million plus population category collecting ₹15,542 per capita – nearly twice the next population category. This indicates that the revenue advantage of larger cities is not simply due to their larger population base but reflects genuinely higher per capita economic activity and tax collection capacity.

Growth rates (2020-21 to 2021-22) tell an even more interesting story: larger cities are not only generating more revenue, but they’re also growing faster than smaller cities. This widening gap indicates that smaller municipalities will require substantially greater support from central and state governments, through increased transfers, capacity-building initiatives, or targeted urbanization programs – to keep pace with the demands of rapid urban growth. Without such interventions, the revenue disparity between large and small ULGs is likely to deepen over time.

Big Cities Under the Lens: Who’s Leading the Way?

Now we know that India’s largest cities are at the forefront of the country’s growth trajectory, with their total revenues far exceeding those of smaller urban local governments. But as the graph below illustrates, there is considerable variation in total revenue even within these major cities.

While population size plays a critical role – Mumbai, as India’s most populous city, naturally generates substantial revenue, the disparity remains significant even when examined on a per capita basis. This suggests that factors beyond population, such as economic activity, tax collection efficiency, and administrative capacity, drive revenue differences among India’s largest cities.

Among the remaining large cities, Chennai reports the lowest total revenue at ₹3,255 crores. However, looking at per capita revenue, Hyderabad registers the weakest performance, with Bengaluru not far ahead.

These contrasts underscore the uneven fiscal capacity among major urban centres, shaped by differences in economic activity, administrative efficiency, local revenue mobilization patterns, and crucially, the extent of devolution of functions from state governments to ULGs.

Ultimately, these figures highlight the importance of examining city finances through multiple lenses; both absolute and comparative metrics are essential to understanding the true fiscal health of India’s urban landscape.

Beyond the City: Mapping Revenue across States

Indian states vary significantly from each other in terms of level of urbanization, political environment, and institutional capacity. These factors significantly influence how cities generate and mobilize revenue.

The state-wise per capita revenue data reveals distinctive regional patterns across India. The most striking is the massive variation that exists across the country, ranging from Assam’s ₹1,525 to Maharashtra’s ₹18,115 – a more than tenfold difference in per capita revenue. Here, Maharashtra stands out dramatically as the highest per capita revenue generator, reflecting Mumbai’s economic dominance.

Southern states demonstrate consistently strong performance, with Kerala (₹7,481), Karnataka (₹4,745), Tamil Nadu (₹4,191), and Telangana (₹3,741) all showing relatively high per capita revenues.

Western states also excel, with Gujarat generating ₹5,839 per capita and Madhya Pradesh reaching ₹5,017. In contrast, northeastern states lag significantly behind, with Assam at ₹1,525 and Mizoram at ₹1,467 representing the lowest figures.

These disparities underscore that revenue generation capacity depends not just on urbanization levels, but critically on the extent of functional devolution and administrative powers granted to ULGs – more urbanized states don’t necessarily generate more revenue if their local governments lack adequate authority and resources.

Conclusion

This analysis reveals a stark reality: India’s urban revenue landscape is marked by significant concentration and growing disparities. Larger cities not only command the lion’s share of total revenue but also generate substantially higher per capita income and experience faster growth rates. Addressing this challenge requires recognizing that state-level decisions about revenue-sharing, functional devolution, and administrative autonomy critically shape urban fiscal capacity. We need to investigate these patterns further to understand how they extend beyond population size to economic activity, and administrative capacity.

These widening gaps raise critical concerns about fiscal federalism and the sustainability of India’s urbanization trajectory. As revenue inequality between large and small cities increase, the challenge ahead involves both learning from high-performing cities and reforming state-level frameworks that govern urban finance.

Mumbai has emerged as a clear outlier throughout this analysis. Stay tuned for an analysis, where we dive deeper into what makes India’s financial capital such a revenue powerhouse.

Note: To ensure comprehensive representation and account for variations in data coverage and quality across cities, the figures presented are based on extrapolated financial data covering all 4,824 cities. Among these, 2,541 cities (approximately 60%) possess 3 years of contiguous data (2019–20 to 2021–22) in Cityfinance platform. Data from these cities have been systematically extrapolated using the ’per capita scaling methodology’ to reflect the financial performance of the complete set of 4,824 cities. Learn more about the extrapolation methodology here.